BUY: Amazon.com | Barnes & Noble | Indie Bound |Powell’s | University of Georgia Press

EXCERPTS: Read excerpts from The Bigness of the World.

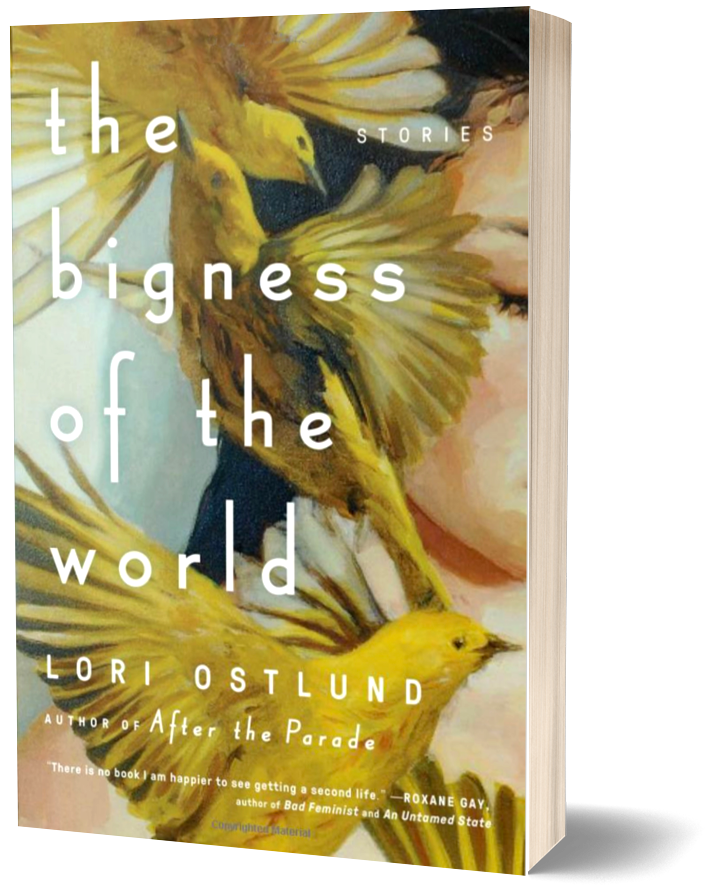

The Bigness of the World

In Lori Ostlund’s award-winning debut collection, people seeking escape from situations at home venture out into a world that they find is just as complicated and troubled as the one they left behind.

In prose highlighted by both satire and poignant observation, The Bigness of the World contains characters that represent a different sort of everyman—men and women who poke fun at ideological rigidity while holding fast to good grammar and manners, people seeking connections in a world that seems increasingly foreign. In “Upon Completion of Baldness,” a young woman shaves her head for a part in a movie in Hong Kong that will help her escape life with her lover in Albuquerque. In “All Boy,” a young logophile encounters the limits of language when he finds he prefers the comfort of a dark closet as he confronts the truth about his parents’ marriage. In “Dr. Daneau’s Punishment,” a math teacher leaving New York for Minnesota as a means of punishing himself engages in an unsettling method of discipline. In “Bed Death,” a lesbian couple travels to Malaysia to teach only to find their relationship crumbling. And in “Idyllic Little Bali,” a group of Americans gather around a pool in Java to discuss their brushes with fame and end up witnessing a man’s fatal flight from his wife.

In The Bigness of the World we see that wherever you are in the world, where you came from is never far away.

Reviews

Fiction Writers Review

“I can’t help but imagine how O’Connor might react to its stories, full as they are of godless homosexuals scattered across the globe, whereas O’Connor’s work is unapologetically regional and almost dogmatically Catholic. Even with this wide discrepancy in subject matter, Ostlund’s book is one O’Connor might have chosen herself, so similar are their aesthetics. In fact, Ostlund’s characters in many ways resemble the ones that O’Connor is always pushing toward their inevitable moments of grace—stubborn, overeducated folks who value rationality and discretion to the point of personal isolation.”

[Read J.T. Bushnell’s review]

“Ostlund’s stories are so freakishly focused and darkly atmospheric that you may find yourself especially noticing your fellow human animals’ oddities in the days after you read them, then stepping back for perspective. Ostlund could ask for no better indicator of this collection’s success.”

[Read Pamela Miller’s review]

“Ostlund, whose work has been included in the Best American and also PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories, is a writer to watch. She constantly delights the reader with the subtlety of her insights as well as the carefulness of her prose, as we find that beneath the comic observations of cultural misunderstanding, or a couple’s quirky habits, lies a genuine melancholy – and the sense that while there is absurdity in reticence, there is sadness in it too.”

[Read Sylvia Brownrigg’s review]

All of us, no matter our age or experience, are trying to grasp the bigness of the world. When we read the work of a writer like Ostlund, it almost seems possible.

[Read Joe Mill’s review]

What Lori Ostlund is able to do that many writers fail to do is capture so authentically realisations, moments of change, and the aching truths within her stories.

[Annie Clarkson’s review / interview]

Overall, this is an impressive collection of stories that range widely from tragic to comic (often within the same story). Ostlund has a keen insight into human behavior that allows the reader to recognize themselves in characters with whom, outwardly, they have absolutely nothing in common. And her writing has an old school quality that draws attention not to her style, but to the characters and their stories, which are always compelling.

[Read Laura Pryor’s review]

One of the most remarkable aspects of The Bigness of the World is how Ostlund explores not only the physical geography of this world but also the intimate inner geographies of her varied characters. These inner lives are detailed with such dense, tightly coiled and precise language it becomes easy, as a reader, to find yourself immersed in their hopes, their worries, their minute obsessions, joys and fears. Ostlund wields language in terribly complex ways building exceptional sentences, long and swollen with nuance and history, creating narratives that take the long way around. Each story holds a certain very smart wit that endears.

[Read Roxane Gay’s review]

The Rumpus

There’s a lot to smile at in The Bigness of the World, Lori Ostlund’s Flannery O’Conner Award-winning collection—but there aren’t a lot of jokes. In fact, over the course of a dozen stories, Ostlund presents all kinds of suffering: death, self-mutilation, jail, child abuse, poverty, and an overabundance of breakups. As the title suggests, Bigness is full of characters confronted with the unmapped and unexpected, with newness and unthinkable difference; even as Ostlund’s characters wish for stillness, shit happens. As the narrator tells us at the end of the title story, “the familiar terrain of our childhood would soon become a vast, unmarked landscape.” In depicting this unpredictable world, Ostlund is forced to leave behind the short story’s generic punch-line structure. While her stories often end with surprises, these endings, happily, never really seem to be the point.

[Read review]

Reviewer Anna Clark reviewed THE BIGNESS OF THE WORLD as a video review for the November issue of The Collagist.

[Watch review]

SAN FRANCISCO MAGAZINE

“The Bigness of the World wastes no time in establishing Ostlund as one of the new front-runners in Bay Area short fiction.”

[Read review]

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, STARRED REVIEW

Ostlund’s remarkable debut collection deftly navigates the treacherous shoals of decaying relationships in which the protagonists often escape to faraway lands in order to find themselves, or, at the very least, their partners. Fate, for the globe-trotting teacher-entrepreneur of “And Down We Went,” takes the form of an untimely bird dropping; in “Bed Death,” it is a Malay waitress who casually takes a sip of orange juice from the narrator’s glass. Ostlund’s artful prose is playfully complex and illuminating, evocative and unsentimental, as in “Upon the Completion of Baldness,” in which the narrator’s girlfriend returns home from a trip completely bald. Remarks the narrator, “the chilly desert air seemed to startle her as though, in that moment, she realized that there was a price to be paid for having no hair, and while I still said nothing, I was happy to see her suffer just a bit.” A specific disenchantment inhabits these stories—the disenchantment of the uncompromising romantic confronted with the evaporative nature of love. Each piece is sublime.

“Reviewers can be very protective of first-time authors. We watch as they emerge like fragile hatchlings into the literary world – hollow-boned and downy soft – and pray that an indiscriminate critic doesn’t stroll by and bite off their head… Not that Lori Ostlund will need much protection. The Bigness of the World, Ostlund’s first collection of short stories, was good enough for the judges of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. She won the prize in 2008… Deservedly so, for Ostlund has an ear, an appendage often ignored by writers in favor of the flashier eye.”

[Full Review]

Set among such divergent places as small-town Minnesota and an Albuquerque airport, a Belizean café and a hotel swimming pool in Java, Ostlund’s Flannery O’Connor Award–winning debut collection depicts sexually and socially repressed Americans. Men and women who wind up feeling displaced when they fail to escape the influence of their past: ineffectual parents, fathers and lovers who disappear, teachers who struggle to connect with their students, and lifelong obsessions with language. In “Bed Death,” two lesbians flee to Malaysia as a couple to teach only to find their relationship crumbling as they are accepted in their new environment. In “All Boy,” a young logophile encounters the limits of language when he finds he prefers the comfort of a dark closet over the struggle to make friends at school. The narrator in the title story, one of Ostlund’s many smart, manner-conscious characters, expresses her fastidious babysitter’s contempt for “the American compulsion toward brevity.” Witty and sharp, Ostlund has crafted 11 surprising and often very funny tales that remind us just how vast the world really is. — Jonathan Fullmer

Excerpts

An Excerpt from a Story in The Bigness of the World. Originally published in Hobart.

Backstory

In a way, this story reflects my farewell to academia, academia being a route I once saw myself going. Within that world, and especially the world of literary theory, which I was enamored of for a time, it is very easy to start creating one’s own script—a script that involves all sorts of asides and tangents that interest the theorist, who then starts to believe that those tangents and asides are the point, or needs to believe that they are the point—and in the process the theorist misses the main point, the real story that is going on under his or her own nose.

I wanted to be that person for a while, and then one day, I came to my senses. I guess I wanted a narrator who was working under those conditions, but applying the process to her own life—with the same result. She misses the point.

Excerpt

At this point, there had been only the vague reports that Mr. Matthers was teaching with both hands held in the air, not fully extended like in a hold up, but partially, with his hands sprouting out just above his shoulders. I began to hear more specifically about this strange behavior from my students, many of whom were in his science classes. One day, while my tenth graders worked at their desks diagramming sentences, which, for the record, I still consider a worthy endeavor, I crept down the hall and around the corner to Mr. Matthers’s room. He was wearing a tan lab coat with Let’s Bake Bread stenciled across the front, standing before the class with his heels together and his toes pointed out at a ninety-degree angle, in what we were taught was the appropriate stance for reciting the Pledge of Allegiance or acknowledging “The Star-Spangled Banner” when I was young. And yes, his hands were aloft, not gesturing or even keeping rhythm with what he was saying but simply floating, perfectly still, as though he had thrown them up in a moment of surprise and forgotten them there. However, that night at dinner, when I informed Felicity that I had gone down to Mr. Matthers’s classroom and witnessed his strange behavior firsthand, she remained dismissive. “Maybe it’s part of a science experiment,” she suggested, chewing as she spoke.

“A science experiment,” I replied incredulously, though I paused to swallow first. “The students say that he teaches the entire class like that. How could it possibly be part of a science experiment?”

“Well, perhaps Mr. Matthers is experiencing problems with his circulation. Perhaps he is simply following the advice of a doctor,” she had suggested next. “Perhaps,” I replied. “But wouldn’t he explain this to the students if that were the case?”

“Perhaps Mr. Matthers is of the opinion that his duty to the students is to explain science,” she replied, getting in the final “perhaps,” though I knew that she did not care for Mr. Matthers either.

An Excerpt from a Story in The Bigness of the World. Originally published in The Georgia Review.

Backstory

This story, like most of my stories, came about because of a confluence of events: my brother and his wife came to visit, and since they too are teachers, we spent much of the visit bemoaning the state of education but also laughing about any number of things, including the fact that when my brother and I were children, the lowest reading group at our elementary school was called the Donkeys. (I don’t think that we thought much about it, though perhaps “the Donkeys” did.)

Around the same time, one of my Brazilian students, a pilot, received word that his friend back home, a fellow pilot, had been blinded when a bird flew into his windshield and shattered it. I had started working on the story by then and one day decided, for the sake of procrastination, to see how many proverbs about ants I could find. I was enjoying Dr. Deneau’s voice and found that he and I shared many pet peeves, including, it turned out, that we both find proverbs irritating, and so the ant proverbs entered the story.

Excerpt

Dr. Dunno. That is what the boys call me, what they write on desks and in bathroom stalls, a play on my name—which is Deneau—and on the fact that, day after day, that is how they respond to my questions. “Dunno,” they say with an elaborate shrug and the limp, unarticulated drawl that has become ubiquitous among teenagers in a classroom setting; they cannot even be bothered to claim their ignorance in the form of a complete sentence, to say, “I don’t know,” a less than desirable response to be sure, but one that does not smack of apathy and laziness and disdain.

They arrive each day with matted hair and soiled faces, a lifetime of wax and dirt spilling from their ears. “Ear rice,” the Koreans call it, referring, no doubt, to the tiny balls that a normal person, one who attends to his ears on a regular basis, is likely to produce—not to the prodigious amounts produced by thirteen-year-old boys oblivious to hygiene. However, I cannot sit beside them each morning as they prepare for school, coaxing them to apply just a bit more soap, to consider a cleaner shirt. No. My realm is the classroom, my only concern that when they leave it, they possess at least a modicum of proficiency in that much-maligned subject to which I have devoted my life: mathematics.

An Excerpt from a Story in The Bigness of the World. Originally published in The Kenyon Review.

Backstory

In 1996, my partner and I moved to Malaysia, where we taught business communications at a school very much like this one. We did not actually live in Nine-Story Building, but our friend Raja did, and so we became familiar with the building, which was the tallest building in town at that time and, thus, a place attractive to jumpers.

Like the couple in the story, we stayed in a seedy hotel where the smoke alarms beeped every few minutes because no one had figured out yet that the beeping meant that the batteries were low. After trying to explain this, to no avail, we spent an afternoon trying to buy replacement batteries—also to no avail. Finally, we were moved to the only beep-free room—and yes, there was a wounded, moaning man outside our door.

We never learned what had happened to him, which is ultimately for the best when it comes to writing fiction.

Excerpt

We met Mr. Mani because we paused on the footbridge that spanned Jalan Munchi Abdullah, a busy street near our hotel, for it was only from up there that the sign for his school, the unobtrusively named English Institute, could be seen. The school, which occupied the second floor of the decrepit building just below us, did not look promising, and when we trotted back down the steps to the street and went inside, it seemed even less so. Still, we presented our resumes to the young woman at the front desk, and she, not knowing what to do with them or us, summoned Mr. Mani from class.

Mr. Mani was a small Indian man in his sixties, no taller than either Julia or I, which put us immediately at ease, and when he smiled, he seemed at once boyish and ancient because he was missing his top front teeth. He did not speak Malaysian English, which we were still struggling to understand, but sounded in every way British, to the point that when he heard our American accents, he winced, which could have annoyed us but instead made us laugh. He studied our resumes at length before explaining, apologetically, that the school provided only enough work for him, though when we met him for dinner that evening, we learned that he rarely spent fewer than twelve hours a day at the school, teaching mornings and afternoons and then, at night, checking homework and attending to paperwork. We discovered also that the empty space created by his missing teeth accommodated perfectly the neck of a whiskey bottle, which spent more and more time there as the night wore on, and after he had consumed a fair amount, he revealed that he stayed late at the school also as a way of hiding from his wife, whom he referred to as “my Queen.”

I do not think that it occurred to him, ever, that Julia and I were a couple, yet he spoke to us without the usual nonsense or innuendo that so often marks discourse between the sexes. He talked mainly about his marriage, which had been arranged, stating repeatedly that he did not question the matchmaker’s thinking in putting together a poor but educated man from Kuala Lumpur and an illiterate woman from the rubber plantation. “After all, we have produced eleven children,” he pointed out proudly, confessing that, given his long hours, he saw them only when they brought his meals or attended their weekly English lessons. His favorite was the fifth child, a girl by the name of Suseelah who loved Orwell as much as he did and loathed Dickens almost as much. In fact, he spoke of Dickens often, always with contempt, and I could not help but view it as a classic example of a man railing against his maker, for Mani was a character straight from Dickens, an affable, penniless fellow who bordered on being a caricature of himself.

When he had consumed the entire bottle of whiskey, he declared the evening complete and insisted on the minor gallantry of walking us back to our hotel, a seedy place that he promptly deemed “unsuitable for two ladies.” At the door, he shook our hands sadly and said, as though the evening had been nothing more than an extended job interview, “My ladies, I am afraid that I cannot hire you.”

An Excerpt from a Story in The Bigness of the World. Originally published in The Bellingham Review.

Backstory

This story came out fairly quickly, except for the ending, on which I spent a fair amount of time stuck. I wrote one ending in which the narrator and her brother became adults, but that changed the focus of the story, and so I did what I generally do in such cases—I set the story aside, unfinished.

Months later, my partner Anne and I visited Point Reyes near Carmel, a stunning place. As we looked out at the ocean, Anne said, “Your mother should visit us. She really needs to see the ocean.”

I grew up in a very small town in central Minnesota, and my mother has never ventured away, which means that she has never seen the ocean. “Why?” I asked. “Why does she need to see the ocean?”

“Well,” Anne said, “How else can you understand the bigness of the world?”

The next day as we were waiting to have our oil changed, the ending came to me in a rush, and we got in the car and drove home, setting aside the other errands of which the afternoon was to be comprised. I made Anne sit in the car while I went upstairs to write; the moment seemed that tenuous to me. That phrase—the bigness of the world—led to the ending and became the title of the story and later, of the entire collection.

Excerpt

Ilsa was plump when we knew her but had not always been. This we learned from photographs of her holding animals from the pound where she volunteered, a variety of cats and dogs and birds for which she had provided temporary care. She went to Weight Brigade only that one time, the time that she met my mother, and never went back because she said that she could not bear to listen to the vilification of butter and sugar, but Martin and I had seen the lists that our mother kept of her own daily caloric intake, and we suspected that Ilsa had simply been overwhelmed by the math that belonging to Weight Brigade involved, for math was another thing that “absolutely petrified” Ilsa. When my parents asked how much they owed her, she always replied, “I am sure that you must know far better than I, for I have not the remotest idea.” And when Martin or I required help with our math homework, she answered in the high, quivery voice that she used when she sang opera: “Mathematics is an entirely useless subject, and we shall not waste our precious time on it.” Perhaps we appeared skeptical, for she often added, “Really, my dear children, I cannot remember the last time that I used mathematics.”

Ilsa’s fear of math stemmed, I suspect, from the fact that she seemed unable to grasp even the basic tenets upon which math rested. Once, for example, after we had made a pizza together and taken it from the oven, she suggested that we cut it into very small pieces because she was ravenous and that way, she said, there would be more of it to go around.

“More pieces you mean?” we clarified tentatively.

“No, my silly billies. More pizza,” she replied confidently, and though we tried to convince her of the impossibility of such a thing, explaining that the pizza was the size it was, she had laughed in a way that suggested that she was charmed by our ignorance.